Cellular phone forensics is a complex subject and can often be intimidating; especially to those who don’t work in the cellular realm every day. However, on a daily basis, there are several self-declared experts in this field who have never attended a training – they have simply possessed a cell phone and felt confident in its use and associated data functions. Matter of fact, these experts can be found in any law enforcement department around the Country. It is simply bewildering the number of law enforcement investigators who jump at the opportunity to conduct their own cellular examinations of their evidence, often under the pretense that they know what they are looking for and can easily access it, saving their departments time, money, and resources – effectively being good stewards of taxpayer dollars. I mean, honestly, why would you pay for something that you could easily do yourself?

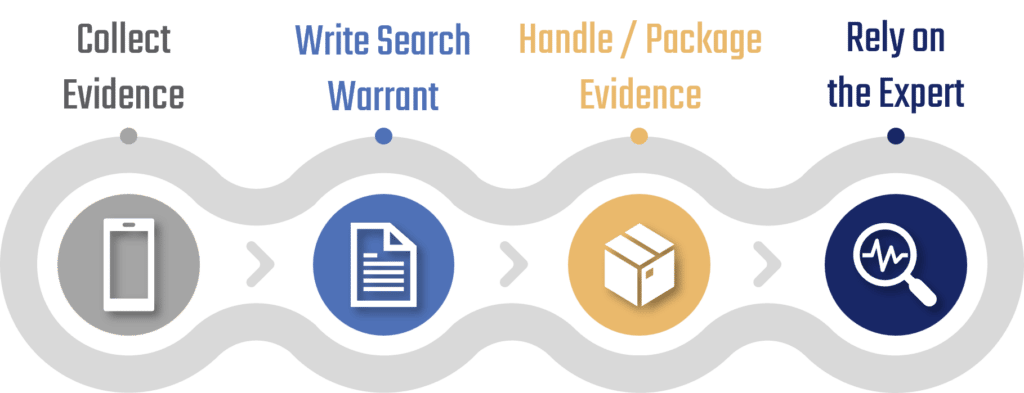

This decision, though often made with good intentions, can also backfire. Let’s compare this very same scenario to DNA evidence. Investigators are trained to collect DNA evidence and then send it off to the experts in the labs to process, identify, and report back any findings. Why would this same process not be adopted for cellular examinations – or any type of digital forensic examination? The role of the law enforcement officer in regards to digital evidence should include: (1) collecting the evidence (in this case cellular devices), (2) writing effective search warrants that will support a lawful and thorough examination of a cellular device by qualified personnel, (3) knowledge of handling procedures to include packaging and shipping the device to a forensic examiner (the scientist of the digital world), and finally, (4) allowing the expert to examine the evidence in a sound forensic manner and environment.

What happens if what you are looking for is right in front of you, but you can’t find it?

Self-declared forensic experts, aka law enforcement investigators, arise from the unknown. These unknowns range from the associated data retrieval costs of involving an expert; uncertainty that the expert can actually recover any data – and if not, the cost associated with the attempt; and the length of time it takes an expert to extract, interpret, and report on the data. And for good measure, let’s throw in the fact that law enforcement investigators have finite resources and limited time frames – and many times – a supervisor that doesn’t fully understand that an expert can help uncover the answers, or in the very least, eliminate any false assumptions.

In most cases I’ve helped with, I find that law enforcement simply stop their investigations at the tip of the iceberg, because they are not familiar with the sheer amount of data that could be retrieved from cellular devices. Most investigators focus their sights on data elements such as contact information, call logs, text messages and photographs. I’ve witnessed this time and time again, especially in cases involving narcotics trafficking and unlawful gun crimes.

For most drug investigators, they are hoping to find a single text message from the drug source to the drug buyer stating that the 2kg of cocaine was delivered to a specific location at a specific date and time, accompanied by a photo of two bricks of cocaine with 2kg written on them; and let’s throw in a picture of a gun for good measure. To wrap up the case, a secondary text message is sent from the buyer to the seller saying “I’ll meet you there.” The cherry on the top would involve the investigator seeing this information before the exchange happens so he could be there to witness the crime.

We all know it isn’t that simple, but yet, law enforcement continues to limit their possibilities by digging for the answer themselves. I am here to inform you that cellular phone forensics can and will uncover a slew of unknown activity that the investigator may or may not have known about. In addition to the common data elements that investigators focus on, I’ll provide a short list of data elements often forgotten:

- Call log information (outgoing and incoming)

- Instant messaging

- GPS locations associated with photographs

- Google searches for the meeting locations or hundreds of other locations

- Chats

- Contacts

- GPS locations associated with the device itself or events done on the device

- Emails

- Installed applications (identification of accounts, cash apps, other sources of communication, etc.)

- Instant messaging

- Passwords

- Social media

- Web history (searches of places, events, map locations, etc.)

- Wireless networks

- Video from various sources (video taken from device, video received from others, video from security systems the phone is synced with, etc.)

- Timelines of events from the device

Though this list is not all inclusive, it gives you a picture of the rapidly changing digital forensic world. Law enforcement run a risk when they decide not to include a digital forensic expert, such risks include – loss of data, altered data (inadvertently or not), and skipping over pertinent data. These issues could render any data inadmissible in court.

It is understandable when law enforcement attempts to do more with less. Over the past few decades, officers have been asked to take on many new roles and tasked with ever-changing responsibilities. Handling, extracting, and interpreting digital evidence should not be one of them – tasks like this should be left to the experts who have extensive training and knowledge in this field.